Craig Murray writes:

I approached Day 2 with trepidation. It was not so much being accustomed to having hopes dashed, as having lived so long without hope that it was hard to know what to do with it. At 5.30am I stopped work for a while on writing up Day 1 and went out to walk down the Strand to the court. There was a slightly bigger crowd than had been there the day before at the same time, and happily it included the heroic volunteers saving my place.

A freezing Easterly wind was bustling down the Strand having come express from Siberia, driving before it what felt like a fair chunk of the North Sea, penetrating through layers of clothing with the ease of a ghost through the walls of St Pauls. I gave the volunteers my opinion of the case so far and what I hoped was a rousing 6am pep talk. They were just astonishingly cheerful in the circumstances. There is a human goodness which can warm from within – I do wish I had some.

Having explained I wanted to publish as much as I could before returning to court, I went back to my Airbnb, where I needed to change all my clothing and even my shoes. I then got back to writing, and dashed off a good few more paragraphs before court, then pressed publish.

I was a little worried that this might be the day I was arrested – my appearance the first day might have thrown the authorities off guard, and I had always thought they would likely think about it a little before acting on the “terrorism investigation” nonsense. But in the event I had no problems at all, and police and court officials continued to be very friendly towards me.

Taking our position in the courtroom, there were still fewer seats available to the public. This is because there was a much larger presence of the “court media”, meaning those London-based journalists with permanent accreditation to the court. They had largely ignored Day 1 as that was Julian’s case; they had however turned up to report the US Government case on Day 2.

I had witnessed precisely the same behaviour at the ICJ Genocide Case in the Hague, where the Israeli arguments on the second day got massively more media coverage than South Africa on the first. The BBC even livestreamed the Israeli case but not the South African, which is a breathtaking level of bias.

So there were fewer spaces available. I was squashed up against the lady instructing the lawyer for the Home Secretary, who was actually extremely nice and kept feeding me mint humbugs as it became increasingly obvious I was struggling against cold symptoms.

James Lewis KC, who had previously led for the US government, was not present. This was unexplained; it is not usual to change the lead KC mid-way through an important case, and judges will generally bend over backwards to avoid diary clashes for them. I have to confess I had rather warmed to Lewis, as I think my reporting showed. I wondered if he had lost faith in his client; it may be of interest that his professional profile lists his most famous cases – but not this most famous case of all.

So his number 2, Clare Dobbin, today stepped up to the lead. She appeared to be on tenterhooks. For a full fifteen minutes before the appointed starting time at 10:30 am, she stood ready to go, her papers carefully spread out around the rostrum. She continually looked up at the judges’ chair as though mentally rehearsing zinging her arguments in that direction. Or imagining becoming a judge; how do I know what she was thinking? Ignore me.

It particularly seemed futile that she was standing there all ready to go while we were sitting around her heedlessly chatting, given that we would all have to stand up too when the judges came in, before resuming our places with a fuss of coughing, turning off phones, knocking over files, squashing sandwiches etc. Anyway there she stood, staring earnestly at the bench. This gave me time to remark that she had notably longer hair than the last time she appeared in this case, and the long blond fibres fell completely straight and evenly spaced, ending in a line of hair across the back of her legal gown that was not only perfectly straight but also perfectly horizontal, and remained so no matter how she moved.

It was the most disciplined hair I ever witnessed. I suspect she had shouted it into submission. Ms Dobbin has an extremely strong accent. It is right out of those giant Belfast shipyards that only ever employed Protestants and which produced great liners that sank more efficiently, and in a more Hollywood-friendly manner, than any other ships in the world.

Someone in the shipyard had taken Ms Dobbins’ accent and riveted on a few elongated vowel sounds in an effort to make it posher, but sadly this had caused cracks of comprehension below the waterline.

However, something had happened to Ms Dobbin. She had been stentorian – I had previously described her as Ian Paisley in a wig. But now it took me several minutes to realise she had started speaking. This did not get better. The kindly Judge Dame Victoria Sharp came up with about eight different formulations in the course of the morning to ask her to speak up, like a school teacher encouraging a shy child at a carol concert. All to no avail.

One thing was very plain. Ms Dobbin had lost her faith in the case she was presenting. She hardly tried to argue it. That was not only in terms of volume. Ms Dobbin made very little effort at all to refute the arguments put by the Assange team the day before. Instead she merely read out large chunks of the affidavit provided by US Deputy Attorney General Kronberg in support of the second superseding indictment.

As judges Johnson and Sharp presumably can read, it was not plain what value this exercise added. Ms Dobbin is not so much in danger of being replaced by Artificial Intelligence, as being replaced by a Speak Your Weight machine. Which at least may have a more pleasant accent.

I should explain “Second Superseding Indictment”. The indictment, or raft of charges on which Julian Assange was first held for extradition, was an obvious load of nonsense flung together and scribbled on the back of Mike Pompeo’s laundry list. However, before the hearings started the US Government was allowed to scrap this and replace it with an entirely different set of charges, the “First Superseding Indictment”.

The rendition hearings started with five days of opening argument at Woolwich Crown Court, in the course of which the First Superseding Indictment was torn to shreds by the defence. Therefore – and please read this three times to overcome the disbelief you are about to feel – after the hearings had started – and gone through the important opening argument phase, the United States Government was allowed to drop those charges, change them completely and present the Second Superseding Indictment with an entirely new bunch of charges based on Espionage and Hacking.

The Defence did not get to change their opening arguments to reflect the new charges, nor did they get the break of several months they requested to study the new charges and respond to them. Nor were they allowed to change their defence witness list, which consisted of witnesses called to rebut the charges now dropped, not the entirely different charges now faced. Yes, you did read that all right. No, I can’t really believe it either. Now, let us continue. This is my very best effort to reconstruct, with occasional help from the kind lady from the Home Office, what Dobbin may have mumbled.

Dobbin opened by saying that the defence had made much of evidence being unchallenged. This was a mischaracterisation. All of the defence evidence was challenged. None should be taken as accepted.

Judge Baraitser, said Dobbin, had shown very considerable leniency in allowing evidence to be heard of dubious relevance. Furthermore there was a nexus of relationships between several of the witnesses, and between some of the witnesses and Julian Assange. Some, including one lawyer, had been previously in his employ. The status and expertise of the witnesses individually and collectively is challenged. Their evidence was directly contradicted by the prior evidence which is contained in the witness affidavits of US Deputy Attorney Generals Dwyer and Kronberg.

This case is not about journalism. It is about the bulk disclosure of classified materials. It is about the indiscriminate publication of unredacted names. That is what distinguishes Wikileaks from the Guardian or New York Times. Judge Baraitser had rightly rejected outright that Assange is a journalist or akin to a journalist.

This is not a political prosecution. The US Administration had changed during these proceedings, but the prosecution continues because it is based upon law and evidence, not upon political motivation.

In Superseding Indictment 2 (which sounds like a very bad franchise movie) the hacking charge is added but the accusations in Superseding Indictment 1 are incorporated. What is alleged bears no relation to the Article X ECHR Freedom of Speech cases submitted by the defence. This case is about stolen and hacked documents, about a password hash hacked to allow Wikileaks and Manning to steal from the United States of America, and about the subsequent publication of unredacted names that had placed individuals at immediate risk of physical harm and arbitrary detention.

The indiscriminately published document files were massive. They included over 90,000 on Afghanistan, over 400,000 on Iraq and over 250,000 diplomatic cables. Assange had encouraged and caused Chelsea Manning to download the documents. The Wikileaks website actively solicits hacked material. “The suggestion Miss Manning is a whistleblower is unrealistic. A whistleblower reveals material legally obtained in the course of employment”. Manning however had illegally obtained material.

Assange cracking the password hash “goes far beyond the position of a journalist”. Judge Baraitser was therefore fully entitled to give full weight to that aspect of the case.

The United States had been obliged to go to great lengths to mitigate the danger that arose to its sources after their names were revealed, Many had been resettled, forced to move. The allegation is that the defendant knowingly and deliberately published the names of the informants.

As pointed out by Deputy Attorney General Kronberg, the charges had been approved by a Federal Grand Jury, after very careful independent consideration of the evidence.

Although this prosecution may indeed be unprecedented, it proceeded along long-established principles. There is no immunity of journalists to violate the criminal law. There is now a specific law against the intentional release of the names of intelligence officers and sources, and it has been ruled that this does not breach the First Amendment. The only material for which Assange is being prosecuted under the Espionage Act is that containing names. That is the difference between this and earlier instances which were or were not prosecuted.

Kronberg stated in his affidavit that there is evidence of people having to leave their homes or even their countries as a result of this disclosure. Several had been arrested or interrogated, and some had disappeared.

The material released by Wikileaks had been useful to hostile governments, to terrorist groups and to criminal organisations. Osama Bin Laden and the Taliban had requested and studied some of the disclosed material.

The judges at this stage were looking much more comfortable than they had the day before. They sat back in their chairs visibly relaxed and smiling. Yesterday they had been discomfited by members of their own class saying things about US war crimes to their faces, which they preferred not to hear. Today they were getting a simple recital of Daily Mail clichés and trigger words that reinforce the Establishment worldview. They were back in their milieu, like plump tropical fish in a tank whose heater had failed yesterday but just been replaced.

Dobbin continued that there was no question of any balance of public interest exercise being required. “The material that Assange published unredacted carries no public interest whatsoever. That is at the heart of the case.”

Judge Johnson asked whether Dobbin accepted the evidence given yesterday that others had published the unredacted material first. Dobbin replied that it was Assange who bore the responsibility for the material being available in the first place.

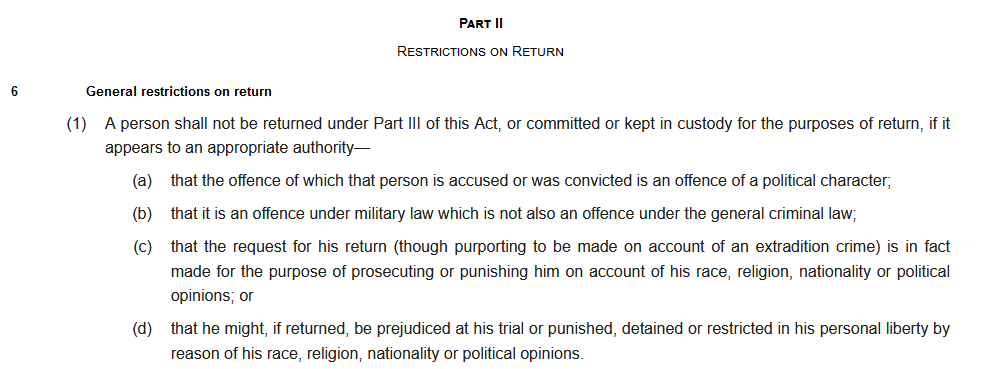

On the question of political extradition, the 2003 Act had transformed extradition law and had deliberately removed the prohibition on extradition for political offences which had been contained in Section 6 of the 1989 Extradition Act (shown here).

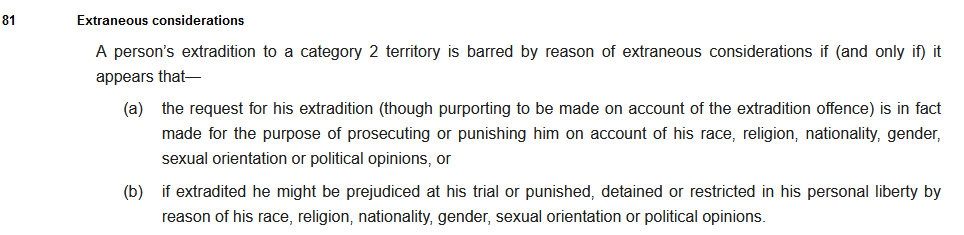

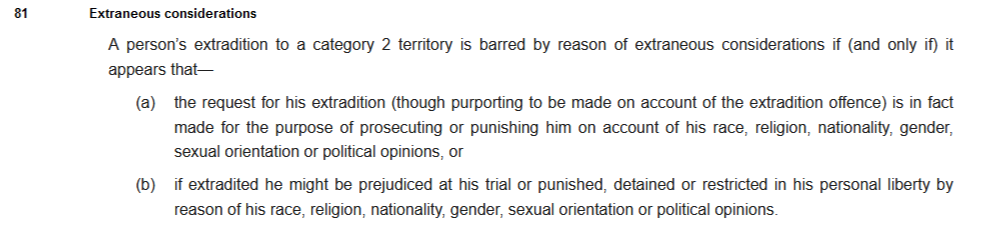

By contrast, Section 81 of the 2003 Extradition Act said this:

The phrase “political offence” had obviously been deliberately removed by parliament, said Dobbin.

Judge Johnson asked if there was any material published by government or anything said by ministers in Hansard which explained the omission. Dobbin replied that this was not needed: the excision was clear on the face of Section 81. If a Treaty contains a provision not incorporated in UK Domestic Law, it is not for the court to reinstate it. The political offence exclusion on extradition is not customary international law.

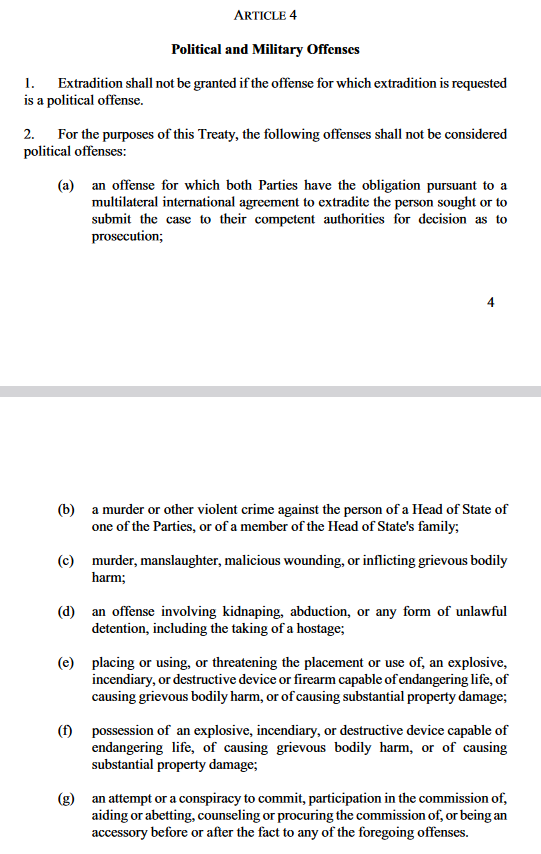

An unincorporated treaty can give rise to an obligation in domestic law, but cannot contradict the terms of a statute. Article 4 of the US/UK Extradition Treaty of 2007 contradicts the terms of Section 81(a) of the Extradition Act of 2003. That Article of the Treaty therefore falls in the United Kingdom, even though enforced in the United States where it does not contradict domestic legislation. Whereas extradition treaties are supposed to be mutual and interpreted the same way by both sides, that does not preclude an extradition by one party in unilateral circumstances.

At this point Judge Johnson was looking at Ms Dobbin with some concern, like a home supporter at a soccer match which his team is unexpectedly losing 3-0, who cannot quite work out why they are performing this badly.

At this point I thought I might introduce a panel so the reader can isolate this vital argument. The question is this. Is this provision of the 2003 Extradition Act at Section 81 (A):

… incompatible with this section of the subsequent US/UK Extradition Treaty of 2007:

… so as to render the latter null and void? That is a fundamental question in this hearing and the assertion made by Dobbin.

If Judge Baraitser’s acceptance of this argument was correct, it of course means that the Home Office lawyers in 2007 drafted a treaty, approved by the FCO lawyers, which neither set of lawyers noticed was incompatible with the legislation the same lawyers had drafted just four years earlier.

It would also mean that the very substantive mechanisms for ensuring the compatibility of treaties with domestic legislation, involving a great round of formal written interdepartmental consultation, all failed too. I have personally worked those mechanisms when in the FCO, and I don’t see how they can fail.

Crucially, Dobbin’s argument depends on the notion that the Extradition Treaty gives a broader definition of what can be a politically motivated extradition, than the Act. So while Assange’s extradition would be barred by the Treaty, it is not by the Act.

But that is obviously nonsense. The entire purpose of the much longer provision in the Treaty is plainly to limit what counts as political under the very broad definition in the Act. It reduces the ground for denying extradition as political; it does not extend it. The fact that even this lengthy list of exclusions does not exclude Wikileaks’ activity is extremely telling.

OK, that’s the end of the panel. Let us return to the hearing.

Dobbin continued that Abuse of Process arguments do not enable the incorporation of unincorporated international treaties. As an example, alleged obligations of the UK under the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child have been found by the courts not to be enforceable in domestic law. It is not accepted by the United States that this is a political offence. But even if it were, Swift and Baraitser are correct in law that there is no bar on extradition for political offence.

The defence had claimed the prosecution purported to be for a criminal offence but in reality was political. This argument must be treated with great caution, because any criminal could argue their offence was politically motivated.

The starting position must be the assumption of good faith on the part of the state with which the UK has treaty relations on extradition. The United States is one of the UK’s longest standing and closest international partners.

The Yahoo article was not fresh evidence. It had been properly considered and rejected by Swift and Baraitser. It was internally inconsistent and included official denials of the conduct alleged. The court must consider the nexus between those making allegations of impropriety and the appellant. Ecuador had rescinded his claim of political asylum and Assange was properly arrested by police invited into the Ecuadorean Embassy. There is simply no evidence that any harm would come to Assange were he to be extradited.

Even accepting the Yahoo article as evidence, that does not affect the objective basis of extradition proceedings. It states that kidnapping was rejected by US government lawyers as it would interfere with criminal proceedings.

It is not journalism to encourage people to break the Official Secrets Act or to steal information. Miss Manning is not a whistleblower but a hacker. Protected speech is therefore not engaged and that entire line of argument falls. Baraitser rightly distinguishes between Wikileaks and the concept of “responsible journalism”. No public interest could attach to the indiscriminate mass release of information.

There are many reasons why the title of whistleblower does not attach to Chelsea Manning. There is no evidence Manning had any specific information she wished to impart or any specific issues she wished to pursue.

Julian Assange did not have to disclose the unredacted material. It was not a necessary part of his publication. The New York Times had published some of the material responsibly and redacted. Assange by contrast arrogated to himself the role of deciding what was in the public interest.

The defence was mistaken in its approach to Article X on Freedom of Speech. The approach in England and Wales is not to consider whether a particular publication is compatible with Article X, but whether a particular criminal charge is compatible with Article X. Plainly the charge was compatible in this case with Article X restrictions on grounds of national security. There was no error in law. In this jurisdiction Assange could also be charged with conspiracy.

Johnson then asked a very careful question. If, in this country, a journalist had information on serious governmental wrongdoing and solicited classified material, and published that material in a serious and careful way, would that not engage Article X?

Dobbin replied that following the decision in the Shayler case, he should have pursued internal avenues.

Johnson pressed that he was not talking of the whistleblower but of the journalist. Would the journalist have Article X protection?

Dobbin replied no, but there would have to be a proportionality test before a prosecution was engaged. (You will recall Dobbin had stated earlier that in this case there was no need for any such balancing test as Manning was not a whistleblower and the material was not in the public interest.)

Dobbin said the USA was at pains to distinguish this unprecedented prosecution from ordinary journalism. This was indiscriminate publication of material. The Rosen case was important because, although in a lower court, it explains why you prosecute Wikileaks and not the New York Times. (This case has come up repeatedly throughout the hearings. Of current interest, it was about AIPAC receiving and using classified information.)

While it was the case that the United States could argue that Julian Assange was not entitled to First Amendment protection due to his nationality, it was not saying it would do that. This was merely noted as an option. This could not therefore be a block to extradition due to discrimination on grounds of nationality under Section 81a.

Johnson interjected that in the affidavit we have the prosecutor clearly saying that he might do this. Dobbin replied that this was “tenuous”. Even if the prosecutor did it, there was no way of telling how it might work out. The judge might reject it. This argument could fall flat in court. This possibility did not offer sufficient foundation to exclude extradition on the basis of discrimination due to nationality. Further this would be about Convention rights that lie outwith the jurisdiction of this court.

At this point Judge Dame Victoria Sharp was looking at Dobbin with great concern, as Dobbin prattled on with a kind of stream of consciousness of meaningless phrases. Judge Johnson attempted to bring her back to reality. Do we have any evidence, he asked, that a foreign national does indeed have the same First Amendment rights as a US citizen?

Well, yes, replied Dobbin. Or perhaps, no. One of the two. She would find out.

With that, Dobbin sat down with a look of great relief. She had got to the end, and spoken so softly that not many people heard what she had said. So not too much damage done. The judges looked even more relieved that she had finished. Prof Alice Edwards, the redoubtable UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, was in court. I wanted to ask her whether listening to Dobbin for more than 15 minutes could in itself be construed as cruel and unusual punishment, but sadly she was seated too far away.

The next KC for the USA now stood up, a Mr Smith, who had been promoted from Number 3 to Number 2 in the absence of Lewis. Smith, from his manner, had no doubts at all about his client’s case, or at least he had no doubts about his fee, which amounts to the same thing. He also had no problem being heard. They heard him in Chelsea.

He said that he wished to address the mosaic of complaints brought by the applicant under Articles IV and VI of the ECHR, relating to fair trial, the rule of law and abuse of process. In the written submissions, the appellant had referred to the system of plea bargaining as enforcing guilty pleas by threatening disproportionate punishment, thus interfering with fair trial. But this argument had never been accepted in any extradition to the United States. In some matters, such as jury selection, the defendant had better rights than in the UK.

With regard to the system of sentencing enhancement with reference to other alleged offences not charged, this could not be abuse of process or denial of fair trial. It was “specialty or nothing”, specialty being the principle in international law that a person extradited could only be charged with the named offence.

As the appellant had noted, the US trial judge could enhance the sentence on the basis of whether the applicant was guilty of further offences, on a “balance of probability” judgment. But this does not mean the defendant is convicted of those further offences. The conviction is solely for the offence charged, enhanced by other conduct. The specialty argument then falls. This was not dissimilar to the UK, where aggravating or mitigating factors might be taken into account.

This could come nowhere near the threshold of a “flagrant” breach of the rule of law required to bring the ECHR into operation. Article 6 (2) would only be invoked if the procedure involved an additional conviction on a new charge. The appellant had also raised the possibility of sentencing enhancement from the information in classified material that would be shown to the judge but not to the defendant or his lawyers. But there was no evidence before the court that showed this would happen in this case.

We now come, said Smith, to the question of grossly disproportionate sentencing, which the defence first raised in relation to Article III of ECHR and they now relate also to Article X on Freedom of Speech. But it is not the norm to impose UK sentencing standards on foreign states. The test is whether a sentencing decision is “extreme”.

The defence had given the estimate of 175 years, as the maximum sentence for each charge, running consecutively. But the defence’s own expert witnesses had given different estimates, ranging from 30 to 40 years to 70 to 80 months.

In his affidavit the Deputy Attorney General had stated that avoiding disparity was a key factor in sentencing guidelines. Miss Manning had been sentenced to 35 years and eligible for parole after one third of that sentence under military law. Kronberg had given other possible comparators ranging from 42 months to 63 months.

Assange stood accused of very serious conduct, for which sentence could be upped by significant aggravating factors. In the UK, Simon Finch had his sentence increased to 8 years for leaking a document which had put national security at risk. By comparison Assange’s alleged offence was not just grave but entirely unprecedented.

Assange and others at Wikileaks had recruited Chelsea Manning and other hackers, encouraged them to steal classified information, had published unredacted names thus putting lives in danger and causing relocation. So none of the range of sentences which had been placed before the court would be grossly disproportionate, from 60 months to 40 years.

Article X could only be applied in these circumstances to a flagrant breach of Freedom of Speech rights. That was not the case. This was neither a whistleblower case nor responsible journalism. It does not engage Article X at all.

Judge Johnson asked for a copy of the sentencing remarks of the court martial in the Manning case.

Ben Watson KC now stood up to address the court on behalf of the UK Home Secretary, although on recent form he could not be sure if that would still be the same person when he got back to the office. He stated that the Secretary of State has no role in supervising the extradition treaty, The substantive decision is for the judges.

He said that it was worth noting that the bar on political extradition had been removed from the European Framework Agreement between EU member states. It was a doctrine “on the wane”.

There was no basis for the court to infer that Parliament was not aware of the difference between section 81 of the 2003 Extradition Act and the bar on political extradition at section 6 of the 1989 Act. See for example the contribution of Prof Ross Cranston MP in the debate on the act (Cranston was both an MP and a former High Court judge).

I suspect that Watson threw this out with confidence that nobody actually would see the contribution of Prof Ross Cranston MP in the debate. But then Mr Watson has never met me. I did decide to see the contribution of Prof Ross Cranston MP in the debate, and this is what he had to say on the subject of political extradition, in the debate on 9 December 2002.

Clause 13 refers to extraneous circumstances. We shall not extradite people where they might be pursued for political or religious opinions. That is a good thing. There is, of course, the question of definition. In the Shayler case, the French court refused to extradite Shayler to this country on the ground that it was a political offence, so there can be disagreement about what extraneous circumstances might entail. However, there is a valuable barrier that will operate in our domestic law.

That rather conveys the opposite sense to what Watson claimed Professor Cranston was saying. Cranston says political offences will still be banned, and it will be for the courts to define them. That is plainly not the same as saying the Act is removing the bar on extradition for political offences.

Judge Johnson now asked Watson a question. The treaty bars extradition for a political offence. So does this mean that if the US receives a request for extradition for a political offence from the UK, it can refuse it, but if the UK receives an extradition request for an identical political offence from the US, it cannot refuse it, and the Secretary of State cannot block it even if they consider it contrary to Article IV?

Watson replied yes, that is the position. He seemed to find nothing troubling in that at all. Judge Johnson, however, seemed to find it a strange proposition.

Watson moved on to the death penalty. Chelsea Manning had not received the death penalty. There was nothing to suggest the applicant faced the serious threat of the death penalty. The fact that the United States had said that Assange could serve his sentence in Australia could be taken as an assurance against the death penalty. So there was no need for the Secretary of State to seek assurances. The United States had suggested Assange faced a maximum penalty of 30 to 40 years.

Judge Johnson then intervened again, and asked if there were anything to prevent the United States from adding offences of aiding and abetting treason or other counts of espionage which do attract the death penalty? Watson replied there was nothing to stop them, but that would be contrary to the assurance received on serving sentence in Australia. There must be a threshold of possibility of the death penalty before the Secretary of State was obliged to seek assurances against it.

Edward Fitzgerald then rose for rebuttal. He was in much more commanding form today, on the attack, scornful of the arguments he was dismissing with a broad sweep of rhetoric.

Edward Fitzgerald KC

The United States had failed to address the point of arbitrariness. Of course it was arbitrary to lock somebody up under an extradition treaty, while deliberately ignoring a major provision of that very treaty that specifically says they should not be locked up. Even if we did ignore this vital provision in the treaty, Assange was still being punished for his political opinions contrary to Section 81 of the Extradition Act.

It had been suggested that the removal of the phrase “political offence” from the 2003 Act was an “express omission”. But there was no evidence produced of that. “You are saying that silence provides by inference the provision of the Act, that disapplies a provision that plainly is actually in the subsequent Treaty”.

It is ludicrous to say the bar on political extradition is out of date. It is not out of date. The UK continues to sign extradition treaties containing this exact same provision. It is in all but 2 of the UK’s over 150 extradition treaties. It is in all US extradition treaties. It is in many major international instruments. Plainly this is abuse of process. As stated plainly by Bingham and Harper “it is abuse to disentitle someone to the protection of the treaty”.

The United States had come nowhere near to meeting the point on the discrimination by nationality, if Mr Assange were not given First Amendment protection because he is not a US citizen. For the US prosecutor to say we may or may not apply this discrimination was no answer, any more than if they said they reserved the right to torture somebody but may not do it.

On enhanced sentencing, this point also had not been met. There was a clear danger Assange would be sentenced for offences with which he was not charged.

Judge Sharp asked Fitzgerald if this point could not block every extradition to the USA. Fitzgerald said no, it should be judged on a case by case basis on the likelihood of this occurring. In this case the court had evidence that the prosecution had not been motivated by the offences charged, but by other alleged conduct. Judge Sharp asked if he meant the CIA Vault 7 leaks. Fitzgerald confirmed that he did.

Mark Summers KC then stood to continue the rebuttal. It was remarkable, he declared in a tone of barely suppressed rage, that counsel for the USA had spoken for hours and never once acknowledged the massive evidence of criminal state-level behaviour by the United States revealed in the leaked material. They never mentioned or acknowledged the war crimes revealed. There had never been any challenge in the court to the witnesses who testified for days that the material exposed state-level crimes.

Mark Summers KC

Summers said that a key United States argument seemed to turn on the notion that what constituted a political act and political persecution under section 81, and the standards of evidence required in judging them, were different in an extradition hearing than applied in consideration of political asylum cases. This was wrong, They were the same. The protected categories in Article 33 of the Refugee Convention of 1954

on account of his race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.

… were in practice identical to the protected categories of the 2003 Extradition Act Section 81:

on account of his race, religion, nationality, gender, sexual orientation or political opinions

There was a reason for this. The protection to be given under the Extradition Act and under the Refugee Convention is identical, and for identical reasons, and to be judged by the same standards.

When you prosecute for the act of publishing evidence of war crimes, the nexus that made this political persecution was entirely plain. Publication of information which exposes a state’s crime is protected speech. The state you exposed cannot prosecute you for that.

We had heard much about Deputy Attorney General Kronberg, but he was not the initiator. This was all ordered from way above his head. The prosecution had been decided at the very top. You cannot discuss the sheep and ignore the shepherd. The prosecution had noted that Trump had praised Wikileaks a couple of times as though that ruled out the possibility that agencies in the United States were plotting to kill Assange. That plainly did not follow.

We had clear evidence both from the Yahoo News article and from Protected Witness 2 that there were plans laid by US authorities to murder, kidnap or poison Assange. What does that tell us about the intentions of the US government, as opposed to the bland claims of Mr Kronberg?

The point of foreseeability had not been countered. There was no effort made to counter it. In 2010 it could not have been foreseen that publication would bring espionage charges against the publisher. It had never happened before. Encouraging a whistleblower to produce documents was definitely not unprecedented. That was an absurd claim. It was everyday journalistic activity, as witnesses had testified. No witnesses had been produced to say the opposite.

Of course it was illegal for journalists to commit criminal acts to obtain material. That had not happened here. But even on that case, it does not render the act of publication illegal.

The release of unredacted names was by no means unprecedented. Daniel Ellsberg had testified in these very hearings that the Pentagon Papers he released contained hundreds of unredacted names of sources and officers. The Philip Agee case also released unredacted names of sources and officers. Neither had resulted in an Espionage Act prosecution, or any prosecution aimed at a journalist or publisher.

The information released revealed war crimes. Article X is therefore unavoidably engaged by protected speech. The Shayler case was being misapplied by the prosecution. That judgment specifically excluded the press from liability for publication. It was about the position of the whistleblower. Assange is not the whistleblower here, Manning is. Assange is the publisher. There is no suggestion whatsoever, in any of the Strasbourg authorities, that the press are to be regarded the same way as the whistleblower. What Strasbourg does dictate is that there must be an Article X balancing exercise with the public interest in the disclosures. No such exercise was undertaken by Baraitser.

The prosecution refused to acknowledge the fact, backed up by extensive and unchallenged witness evidence, that Assange had undertaken a whole year of a major redaction exercise to avoid publication of names which might be put at risk. This year was followed by one of the media partners publishing the password to the unredacted material as the chapter heading in a book. Then Mr Assange made desperate efforts to mitigate the damage, including by phoning the White House. This did not accord at all with the prosecution narrative: “At best, Mr Assange was reckless in providing the key to Mr Leigh”.

Several others had then published the full, unredacted database first, including Cryptome. None had been prosecuted, yet more evidence that this prosecution was unforeseeable.

There was, however, no evidence given of harm to any individual from the disclosures. What had been created was a risk. You had to set against that risk the proposed sentence of 30 to 40 years in jail suggested by the prosecution. The guidelines say “rest of life”. Chelsea Manning was given 35 years. Evidence had been given that 30 years was a “floor not a ceiling”. A sentence like this for publication “shocks the conscience of every journalist around the world”.

For what? For revealing state-level crime including torture, rendition, waterboarding, drone strikes, murder, assassination, strappado. Strasbourg regards revelation of these state-level crimes as extremely important. The court has ruled revelations of such abuses as clearly covered by Article X. Leaks had the capacity to stop such abuses, and in some cases actually had. The exposure of major international criminal wrongdoing outweighs the risk created by revealing the names of some of those involved in it.

Dame Victoria interjected that some of the names were of people not involved in criminal wrongdoing. Summers accepted this but said “it is just not tenable to argue, as the prosecution does, that there is no public interest whatsoever in the publications”.

Turning to the issue of capital punishment, the Home Office contended that there was “no real risk”. But it was admitted that Assange could be charged with a capital offence. This exercise is not a risk assessment. The law says that in circumstances where the death penalty might be imposed, there must be an assurance sought against it. “We don’t understand why there is no routine assurance against the death penalty provided in this case. If there is no risk, then surely there is no difficulty in providing the assurance”.

Then, all of a sudden, the hearing was over. The judges stood and left through the door behind them. Five minutes later they were back and reserved their judgment, asking for various written materials to be provided, with a last deadline of March 4. Then they left and it was over.

I am conscious that this account flows less well and reads much more bittily than the account of day one. That is simply how it was. On the first day, Assange’s legal team set out a planned and detailed exposition of the case. On the second, the USA and Home Office responded, and did so in rather disjointed fashion, essentially just reiterating the accusations. There was little legal argument as to why Baraitser and Swift had been right to accept them. The rebuttal was thereafter a series of quickfire returns on individual points.

It was impossible not to note that the judges were distinctly unimpressed by some elements of the prosecution. The possibility of discrimination by nationality over applying the First Amendment appears to be an argument to which the judges were searching in vain for an adequate answer. They were also plainly dissatisfied with the lack of an assurance on the death penalty.

But the British security state is never going to accept that the publication of state secrets is justified where it reveals state crimes, and the judges were desperate to hang on to the ruse of avoiding that question by saying this is only about the publication of names of innocent sources. They are also never going to entertain the wider criticisms of the US system such as sentence enhancement.

So my prediction is that a further appeal will be allowed, but only on the narrow grounds of discrimination by nationality and the death penalty. If their hand is thus forced, the Americans will produce an assurance against the latter and the appeal will be on discrimination by nationality.

That appeal will be scheduled for the Autumn, and its result dragged out until after the US election to avoid embarrassment to Biden. That is my best guess of what happens next. Of course all the time the Establishment has achieved its objective by keeping Julian in a maximum security jail for longer.

The point in the whole proceedings which struck me most strongly, was that in the initial hearings the US was keen to downplay the possible sentence, continually emphasising 6 to 7 years as likely. Now an earlier decision has removed considerations of US prison conditions and Julian’s health from the case, they have radically changed tack and were emphasising repeatedly 30 to 40 years as the norm, which is in effect a rest-of-life sentence. That shift, together with the refusal so far to rule out the death penalty, gives a measure of the ruthlessness with which the CIA is pursuing this case.

My apologies for the delay in producing this report. I caught quite a serious chest infection, I think from the cold and wet in London those days, and was really very ill.

No comments:

Post a Comment